Paper Doll Contemplates the Future of Paper: Art, Music and Medicine

Our periodical forays into the future of paper are usually part of the Paper Doll Organizing Carnivals, but I’ve got so many goodies lined up for next week (a time when Thanksgiving travel and preparations will already be dividing everyone’s attention) that it seemed better to focus on the future today, and shiny, happy organizing delights next time.

A MUSEUM FOR PAPER

Just a few days ago, the culture section of the UK newspaper The Guardian ran a thoughtful piece entitled, “Can Paper Survive the Digital Age?” (We should pause a moment pause to recognize the absurdity of a blog — a piece of digital real estate — referencing a newspaper’s digital site, opining on the dubious future of paper. Moving on now.)

The columnist Ian Sansom, author of Paper: An Elegy, is known for reflecting on the paradoxical qualities of paper. After all, it’s both durable (historically) and vulnerable (to the elements and to growing user disinterest). Sansom discusses the role of paper in art, from Matisse to Miro to the modern paper art of Gordon Matta Clark, then digresses into other artistic ventures, including Pixar film creations like A Bug’s Life and Ratatouille. Architecture and literature do not escape his gaze in the evaluation of the future of paper, either.

Various bloggers were uncomfortable with Sansom’s approach, particular his notion that to prove the ongoing relevance of paper, a national or international museum, on the pattern of The British Museum, should be created in homage to paper. Of course, there are already museums for paper, from the Robert C. Williams Paper Museum in Atlanta to Japan’s Paper Museum to the Paper Discovery Center in Appleton, Wisconsin.

The problem, of course, is that for many, museums stultify. They entomb. The bore. To ensure paper the respected role it deserves in international appreciation, something more lively than a standard museum would be needed. Perhaps something along the lines of the remarkable and interactive Newseum in Washington, DC, a living tribute to journalism (including daily newspapers), would be appropriate.

The irony, of course, is that museums grow and strengthen their reach by expanding from the confines of their physical locations via far-flung visitors’ digital explorations.

Finally, I was still captivated by Sansom’s statement that:

We consume more paper, pound for pound, than any other product, food included. We are paper omnivores. We devour it: any kind, from anywhere.

As a professional organizer who specializes in paper, this description prompts me to see the piles of papers that haunt my clients’ spaces in a new light. It’s as though they were culinary masterpieces and sad leftovers, meals in progress and barely-chewed bits hidden in crumpled napkins. It’s vivid, apt and a bit prone to causing indigestion.

PAPER AND MUSIC

Although I love organizing paper, I’m happy for every digital solution that improves upon paper standards. So, I was delighted to read that the Brussels Philharmonic orchestra will be going paperless. The orchestra is replacing traditional sheet music with 100 individual Samsung Galaxy Note 10.1 tablet computers loaded with NeoScores music software.

Functionally, musicians can note the music director’s or conductor’s instructions and changes, record personal notes and highlight pertinent information, save the notations and share them with other musicians. No more fine erasure crumbles or illegible scribblings. No more coffee-stained music sheets that curl at the edges or blow off the music stand.

For anyone who has ever been a musician (or loved one), you know that page-turning carries with it the potential for fumbles or catastrophes. But the Galaxy Note has a special concert mode that is likened to “flight mode” on cell phones. The feature allows musicians to program a setting which lets them securely swipe pages without accidentally skipping ahead in the musical piece.

Organizationally, this all means that the orchestra can reduce storage space and costs. And, from a financial perspective, the change from sheet music to digital will save the orchestra close to €25,000, or $35,528.

Of course, I wouldn’t expect your nearest middle school orchestra to jump on the bandwagon. Samsung donated these one hundred Galaxy Notes to the Brussels Philharmonic, which is certainly good marketing for both of them. I imagine getting enough of these for all the seventh-grade tuba-players, violinists and flautists will require more than a few bake sales, so I’m fairly confident that sheet music will be around for a while.

MEDICAL ADVANCES…ON PAPER

In medical circles, the big issue these days is EMR, or electronic medical records. Last December, at the mHealth Summit, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius provided a clear-headed understanding for the need to bring medical practices into the 21st century. So now, doctors who have happily (or grumpily) scribbled notes on paper charts or even dictated their charting wisdom for the benefit of medical transcriptionists are coping with the learning curve required to modernize their electronic charting skills. As the The Washington Post wrote last week,

Technology has changed most industries in recent years, but many doctors’ offices still run as they have for decades, with receptionists requesting faxed paperwork and physicians leafing through thick manila folders with years of scrawled medical history stapled inside. Medical students may now be accessing textbooks on their iPads, but much of “health care has stubbornly held onto its cabinet and hanging files,” as Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius remarked at a conference last year.

Some physicians have jumped at the chance, installing computers in treatment rooms — the best of the touch-typists are able to maintain eye contact with patients as they cursor around the screens, selecting short-hand diagnostic codes and text-expanding pre-created phrases. Other medical practitioners have taken to using tablet computers to keep up with their charting, adding notations as they move from room to room.

However, as the New York Times reported last month, the very issues described in “The Ups and Downs of Electronic Medical Records” are making for a shaky transition. Some of it is surely whining — just as white-color executives in the late 1980s and 1990s bemoaned the loss of secretaries and the obligation to master word processing and spreadsheets on their own, I’m sure some doctors would rather focus more on healing and less on trying to figure out why they’re repeatedly directed to click F7 to resume what they were doing in the first place.

Beyond cranky resistance to change, learning curves take time, and doctors seem to have less and less time these day. And certainly there must be some concern from a medical perspective. Computers, and especially text-expanders, macros and short-cut codes save time, but human error via “fat fingers” are more likely to cause errors that are less likely to be caught than if a physician had to hand-write a long diagnostic explanation in Latin. And, of course, there are, as with anything digital, concerns about privacy.

All this said, Paper Doll has faith that the digitization of medical records will improve medical care and organization of medical information, and decrease health care costs…eventually. Until then, I’m pleased to see paper making new and unusual strides in the medical realm.

Just a few days, ago, David Hill at SingularityHub wrote about the use of an inexpensive, paper-based diagnostic test that can assess liver health in only 15 minutes from a single drop of blood. The test measures the presence of liver enzymes without requiring a lab or medical instruments.

It seems almost amazing that all that is needed is an ink-jet printer loaded with wax ink, which prints a specialized pattern on two sheets of paper. The reagents that react with liver enzymes are printed on one sheet; the other receives dyes that change color if a reaction occurs. Then, the two pieces of paper are heated and fused together, creating “channels” that work like mini test tubes in which the reactions occur. Finally, a plasma filter is added and everything is laminated together and cut into squares.

Once a blood drop is added, the color change can be viewed by the naked eye or scanned into a smart phone for improved accuracy and analysis. Liver damage or disease can be diagnosed or ruled out in a quarter of an hour!

Harvard Professor George Whitesides developed this system, and supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, created the non-profit Diagnostics for All to provide “low-cost, easy-to-use, point-of-care diagnostic devices designed specifically for the developing world.” Among Diagnostics for All’s innovations is a paper-based microfluidic diagnostics kit enabling screening for preeclampsia, anemia, and abnormal glucose levels for the detection of high-risk pregnancies.

These are just some of the many paper-based medical diagnostic advances. The approach started with an older format made from nitrocellulose, where an adhesive plasticky membrane has been used by all kinds of medical researchers to detect antibodies, proteins, and DNA — it’s the basis for store-bought pregnancy tests.

But tech blog Futurity.org explains that there’s a way to coat common paper, the same kind sold at office supply stores and probably sitting in your printer right now, so that while it’s smooth to the touch, it would actually be “sticky” to medically-related chemicals. Daniel Ratner, assistant professor of bioengineering at the University of Washington, developed the method for using an inexpensive industrial solvent, divinyl sulfone, to make paper adhere to “medically interesting molecules.” It’s expected that this new method might be able to inexpensively text for diabetes, influenza, malaria and other medical conditions and diseases.

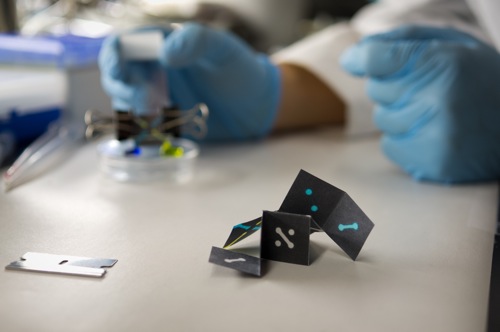

And there are more breakthroughs in paper medicine. Earlier this year, chemical researchers at the University of Texas developed a 3-D paper sensor that can be printed on a standard office printer, folded, and used to test for things like malaria and HIV…for about ten cents per printout!

2012 Alex Wang

Unlike the pregnancy tests on nitrocellulose described above, these 3-D sensors — created from the simple origami-like folding of the papers — can test for a larger number of chemical substances over a smaller surface area and thus provide results for more complex kinds of medical tests.

While these paper advances would be used primarily in developing nations where hospitals and medical labs are few and far between, the implications are impressive and immeasurable. Without the need for the “clutter” of materials for expensive lab tests, diagnoses will be made more quickly, treatment plans clarified and more lives saved — something that would have been science fiction just a few years ago.

What a cool future for paper!

I love what you guys are up too. This sort of clever work and coverage!

Keep up the great works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to our blogroll.

my page … decorating (houseofhomecraft.blogspot.com)