Paper Doll Starts a Taxing Conversation–The Subject of Brackets

Song lyrics. (“Hold me closer, Tony Danza,” indeed.)

Turns of phrase. (Seriously, it’s “I couldn’t care less.” If you could care less, it would mean you cared some amount at all. And aren’t you trying to point out that you really, really don’t care?)

How things work. (When I was a child and saw PaperMommy adjust her rear-view mirror to keep the bright lights of the cars behind us out of her eyes, I assumed adjusting the mirror somehow reflected the brights back at the drivers, alerting them that they needed to somehow reduce the glare. I still think we need an invention like that.)

While in conversation with some very well-versed, knowledgeable folks, I was recently surprised to learn how many people are confused by brackets.

No, not those brackets. We’re a bit early to be talking about March Madness. Though, if you need one, there’s a downloadable 64-team tournament bracket template here.) Rather, I’m talking about the term “tax bracket”. It seems many folks think that if you’re in the 25% tax bracket, that 25% of what you earn each year goes to taxes. That’s not how it works.

[Note: This is not the venue to argue tax reform, flat taxes or political positions. It’s merely an opportunity to make sure we all understand how we are taxed on the little green pieces of paper we earn. So no crankiness in the comments section, OK?]

Let’s start with the basics. For 2010, for singletons like Paper Doll, it works like this:

If you made any money at all, up through but not exceeding $8,375, then you’re in the 10% tax bracket with regard to FEDERAL taxes. That means, on whatever taxable income you have, Uncle Sam will tax you at 10% of the amount. So yes, in that lowest tax bracket, all of your income is being taxed the same amount as your bracket — 10%.

Of course, even that is quite simplified. Our system isn’t set up for us to pay taxes on everything we make. Thus, the 10% tax bracket isn’t levying a tax on 10% of what you made, per se, but on 10% of your adjusted gross income, which is a fancy way of saying “the total (gross) amount you earned, minus deductions and exemptions”.

So let’s say you made the highest amount ($8,375) in that lowest bracket; then you’d be taxed $837.50. But what if you made more? Here’s where it changes.

If you make between $8,375.01 and $34,000, then you’re in the 15% tax bracket. But wait…that doesn’t mean you’ll be paying 15% on everything you made (or, again, more correctly, on your adjusted gross income).

Let’s say your adjusted gross income is the highest possible in this category, $34,000. 15% of that would be $5,100, but that’s NOT what you’ll pay in taxes. Instead, you’ll pay 10% on the first $8,375 (i.e., $837.50) plus 15% of the amount over $8,375. The difference between the amount up to which you’d pay at the 10% level ($8,375), and the total you made ($34,000), is $25,625.

So, if you made $34,000, you would pay:

10% on the first $8,375 (.10 x $8,375 = $837.50)

+

15% on the next $25,625 (.15 x $25,625 = $3,843.75)

= $837.50

+$3843.75

————–

= $4681.25

Remember how I noted that 15% of the total $34,000 would be $5,100? Well, $4681.25 is $418.75 less than 15% of the total. Sure, it’s not king’s ransom, but if you were going along thinking you were going to be paying 15% on everything, that’s good news.

Thus, your tax bracket refers to the highest percentage at which your last dollar earned will be taxed, and not the level at which all of your (adjusted gross) income will be taxed.

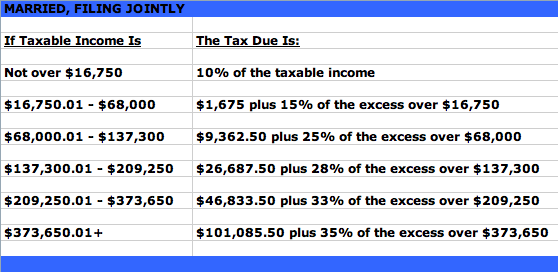

Obviously, deductions and credits and exemptions (oh, my!) play a big role in determining one’s adjusted gross income. Also, to get a general idea of what taxes one might pay on that adjusted gross income, filing status plays a major part. There are separate tax bracket charts for those who fall into each of the following situations:

1) Single — If you were legally separated (or divorced) at the end of the calendar year, you can file as single.

2) Married, filing jointly — This category, not surprisingly, is for married couples pooling all of their income and paying taxes based on their total incomes and combined available deductions. You must have been married on the last day of the year to select this filing status.

3) Married, filing separately — Although this is usually disadvantageous from a financial perspective, it’s sometimes wise or necessary for married couples to file separately. For example, if one spouse suspects the other of tax evasion, he or she can file separately and avoid liability for any taxes, penalties and/or interest that would be due if the other spouse’s evasion were found out. Also, if one spouse owes taxes while the other would get a refund (and the spouses strictly separate their finances), or if a couple is separated, but not yet divorced, filing separately may be necessary.

4) Head of Household — If you are not married but can claim a dependent for at least one half of the tax year, Head of Household status can be advantageous, because the tax rates are lower than with the “Single” category and the standard deduction is higher.

5) Qualifying Widows/Widowers with Dependent Child(ren) — This is the category for anyone who is unmarried, has cared for a dependent for more than half of the tax year and whose spouse died within the past two tax years. It provides the same advantages as “Married, filing jointly”.

The 2010 tax rates (which did not appreciably change from 2009) are further detailed in an IRS PDF.

Of course, all of this refers solely to federal income taxes. State income taxes have their own particular flavors of rules and number of brackets. Some states have no income tax (like Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington and Wyoming), while others (New Hampshire and Tennessee) only levy tax on dividend- and interest-based income and not earned income. Some states allow personal exemptions and/or deductions for federal income tax payments; others have no allowances.

Tax brackets at the state levels range from one flat tax percentage for everyone (in Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Utah) to twelve separate brackets in Hawaii (edging out Missouri’s ten, and Iowa and Ohio’s nine, brackets). Income brackets range from Alabama’s low of $500 up to Maryland’s $1,000,001.

So, it’ll come as no surprise to you that taxes are complicated. In the coming weeks, we’ll look at some ways to avoid scams and get help with preparing your taxes to ensure they are done accurately and so that you do not miss out on any opportunities.

Follow Me